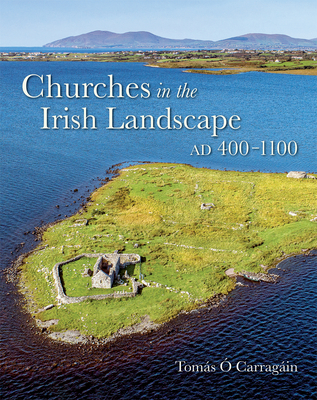

The earliest churches, founded AD 400-550, tend to be positioned in royal and assembly landscapes, often already places of power in prehistory. Clearly, in this period of religious diversity and hybridity, substantial sections of the elite chose to accept, or at least to tolerate, the new religion. In the long run these churches often lost out to later monastic foundations. Because these were further from core royal lands they could be granted the large estates on which their wealth was based. Never before had so much land been owned by undying institutions. This is the first archaeological study to explore how this led to new ways of perceiving, settling and managing the Irish landscape. It also considers the numerous lesser sites established outside these estates in the period 550-800. Evidently, founding churches was not the preserve of kings. People of middling status also had the freedom to do so, while maintaining an attachment to parallel beliefs and practices of pre-Christian origin. In the period 800-1100, social change led to the abandonment of some of these lesser sites, while more substantial community churches began to exert a greater gravitational pull. This shows that the later medieval parish system was grounded in earlier expressions of community.